Brexit briefing: EU migration

EU and non-EU migration into London and the UK

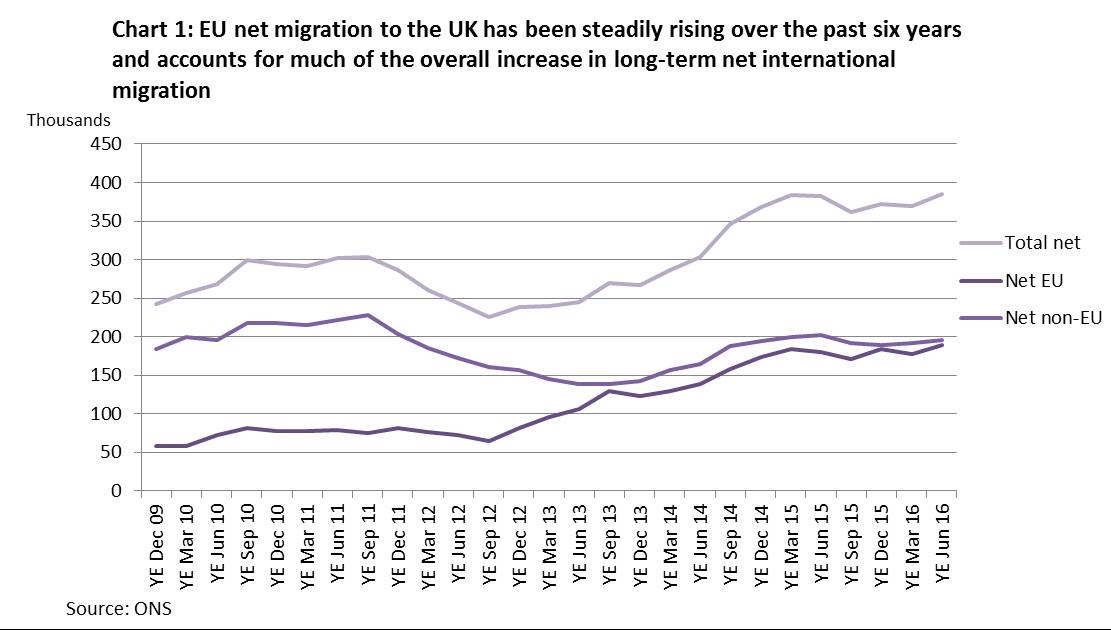

Long-term international migration to the UK has increased in recent years. Total long-term net migration (i.e. inflows minus outflows[1]) into the UK has risen from 268,000 in the year ending June 2010 to 385,000 in the year ending June 2016 (see chart 1).[2] This is considerably higher than the government’s net migration target of “tens of thousands”.

EU net migration to the UK has been steadily rising over the past six years and accounts for much of the overall increase (see Chart 1). According to long-term international migration estimates, EU net migration was 189,000 in the year to June 2016 (up from 72,000 in the year to June 2010) compared with non-EU net migration of 196,000 in the year to June 2016 (the same figure as was recorded in the year to June 2010); data indicate much of the rise in immigration from the EU is due to increasing numbers of migrants from Romania and Bulgaria.[3]

Work is the main reason for EU migration: 38 per cent of EU nationals migrate to the UK with a job offer, compared to one in five non-EU nationals. In the year ending June 2016, there was a 34 per cent increase in the number of EU nationals migrating to the UK to look for work, compared to the previous year.[4]

Short-term migration[5] has also been increasing. According to estimates by the ONS, there were 1.2 million short-term immigrants[6] arriving in England and Wales for a minimum of one month in the year ending June 2014: an increase of 110,000 compared with the previous year.[7] The majority of short-term immigrants do not travel for work but for other reasons such as holidays and visiting family and friends. And almost three quarters leave within three months, with the remaining leaving within 12 months. Of those short-term immigrants that do travel for work, almost all (91 per cent) arrive from the EU (125,000). In the year ending June 2014, there was a 33,000 increase on the previous year which was largely a result of immigration from Romania and Bulgaria (29,000 in 2014 compared with 12,000 in 2013).

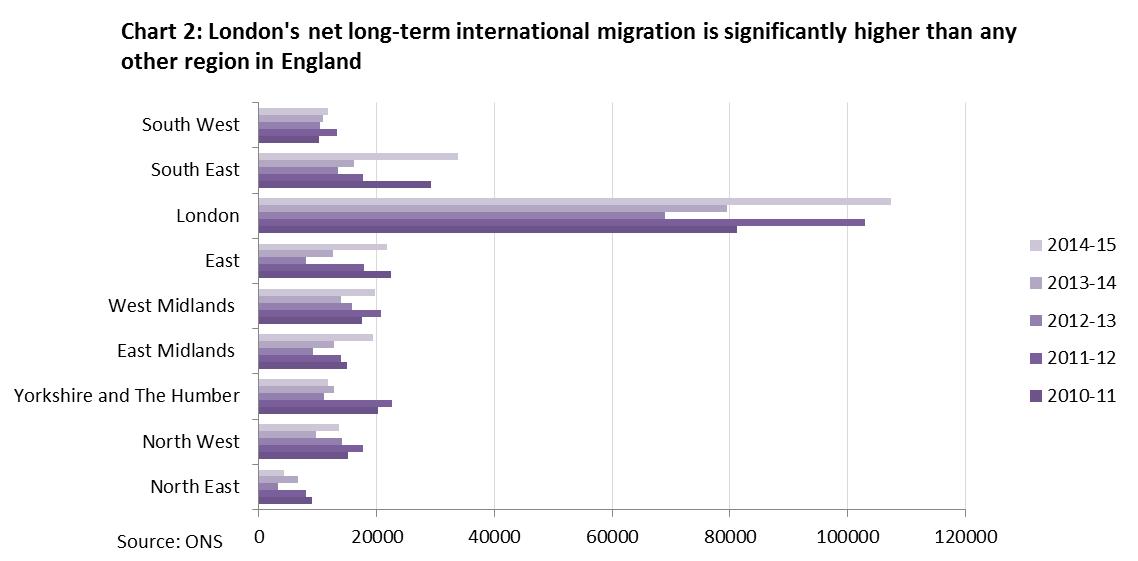

London’s net long-term international migration is significantly higher than any other region in England. London’s net migration of EU and non-EU nationals was 130,000 in 2014-15; a 25 per cent increase on the previous year. Excluding figures for the South East, London’s net migration was larger than all other English regions combined (see chart 2). London’s short-term migration was also considerably higher than other regions: 60,000 in 2013-14; a 45 per cent increase on the previous year.[8] There is an even split between those short-term immigrants that come to London to study and those that come for work.[9]

The International Passenger Survey estimates of long-term migration are lower than the number of National Insurance number registrations for EU nationals. It is unclear whether this disparity reflects short-term and seasonal migration (long-term international migration statistics only capture people moving for at least a year) or other factors such as under-recording.[10] The ONS state the International Passenger Survey is the best source for measuring long-term international migration.[11] This is important because public services become underfunded if government does not accurately record the demands being placed on them.

Foreign students could be excluded from any future UK net migration target. Students who stay for more than 12 months are counted in the same way as those who come and go for other reasons. The number of people immigrating for more than 12 months to study was estimated to be 163,000 in 2016 (a 15 per cent fall on the previous year and the lowest estimate since December 2007). Around three quarters of students are non-EU nationals. And while student numbers would still need to be included in official statistics, commentators have argued they should not necessarily form part of any government target.

There are a number of arguments for and against removing students from the target. The main argument in favour is students are temporary and should not be treated in the same way as people who are more likely to settle permanently. George Osborne, the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, recently said it was “not sensible” to include foreign students in the target because they were temporary, and because education is one of the UK’s biggest exports.[12] Deputy Mayor for Business, Rajesh Agrawal, said the Mayor would “challenge any kind of visa regulations that might hinder international students coming to London.”[13] The main argument against is students still bring short-term demand for temporary housing, transportation, and other services where there are pressures.

London’s share of foreign nationals is considerably higher than any other UK region.[14] In 2015, almost a quarter of London’s population was non-UK born compared to one in ten across the rest of the UK. London’s share of EU nationals is also higher: 12 per cent of London’s population compared to four per cent in the UK in 2015.[15]

It is too early to tell what effect the EU referendum result has had on EU migration. The latest migration statistics cover the quarter ending June 2016 and so do not capture developments post-referendum. However, there is no evidence of any substantive change in net migration in the period leading up to the EU referendum.

Anecdotally there have been reports of EU nationals planning to leave. The government said it would not guarantee the rights of EU nationals to stay in the UK until the status of EU expatriates were confirmed, which has increased uncertainty. According to a survey of its EU readership by the Financial Times, two-fifths of respondents said they were planning to leave within the next two years.[16]

One driver for this si the drop in the value of Sterling, and long term improved economies in some countries of origin, such as Poland. It is less attractive for EU workers in the UK if remittances sent home to support families are worth 11% less due to the drop in the exchange rate.

The process of identifying and registering EU nationals eligible to stay in the UK would be lengthy and complex. Jonathan Portes, senior fellow of UK in a Changing Europe, said the lack of proper records meant it would be impossible to apply a cutoff point from the date of the EU referendum. He said: “we do not have a definition of residence or proof of residence for people who have been here.”[17] He said the government needed to start the process immediately because of the time it could take to decide which of the three million EU nationals could stay in the country.

EU migration and London’s labour market

A significant number of jobs in London are carried out by EU-born workers.[18] In 2015, around 12 per cent of the five million jobs in London – some 600,000 jobs – were held by workers born in EU countries.[19] In comparison, five per cent of the jobs in the rest of the UK (excluding London) were carried out by EU-born workers. There are 30,000 Polish owned businesses in the UK as well as a further 60,000 Polish self-employed workers registered with HMRC.

EU-born workers are employed in a wide range of jobs in London. While a sizeable proportion of EU-born workers (roughly a quarter in 2015) are employed in elementary occupations (e.g. manual labour), many are also employed in professional occupations and senior-level positions (one in five in 2015).[20] This balance is in contrast to the rest of the UK where EU-born workers are mainly employed in low-skilled occupations.

Certain sectors in the capital are especially reliant on EU-born workers. Roughly a third of employees in the accommodation and food service activities sector (79,000 jobs) in 2015 were born in EU countries. Similarly, around a quarter (25 per cent, 88,000) of all workers in construction in London are EU-born workers.[21] The NHS and the tech sector also employ a sizeable number of EU nationals. Roughly one in ten NHS workers in London are from the EU,[22] and according to data from Tech London Advocates, a lobby group, around a third of those working in London’s tech industry are EU nationals.[23] Dr David Lutton, Director of Policy, London First, told the Economy Committee in December 2016 that “50 per cent of the top tech start-ups were actually founded by non-British nationals, people from the EU.”[24]

London is comparatively more reliant on EU workers across all sectors than other regions in the UK. While a quarter of jobs in construction in London are filled by EU workers, only four per cent of construction workers in the rest of the UK are EU-born. London also has a higher share of EU workers in accommodation and food service activities (32 per cent versus nine per cent) and administrative and support service activities (20 per cent versus seven per cent) compared to other UK regions.[25]

Despite immigration rising, immigrants do not account for a majority of new jobs. According to research by the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, the immigrant share in new jobs (around 18 per cent in 2014) is broadly the same as the share of immigrants in the working age population (15 per cent). While the number of immigrants has grown alongside the number of people in employment, data on hiring shows the actual immigrant share in new jobs (the share of immigrants in jobs that have lasted less than three months) is broadly the same as the share of immigrants in the working age population.[26]

In May 2016, the London School of Economics reported that the effect on pay of low skilled workers was minimal: the effect was measured at less than 1% over 8 years. Far greater pressure on pay came as result of the 2008 recession and slow recovery. Moreover, HMRC figures show that EU migrants who arrived in Britain in the last 4 years paid £2.54 billion more in tax and National Insurance than they received in benefits. The Office of Budget Responsibility estimated their contribution helped grow the economy by an extra 0.6% a year.

CIPD research highlights the positive role of EU migrants in enabling organisations to find the skills they need to grow. It found that organisations which employ EU migrant workers are more likely to report that their business had been growing over the previous two years (51%) than organisations that did not employ migrant workers (39%). Employers in low-skilled sectors were particularly positive about the contribution EU migrants made to their organisations’ performance.

The research also shows that employers who employ migrant workers are also more likely to invest in training for the wider workforce and provide apprenticeships than employers who do not employ them. The CIPD argues that this strongly suggests that most employers who employ migrant workers are not doing so to cut costs on training and development, but as part of a broad approach to addressing recruitment difficulties and skills shortages. The CIPD also argues that there is a strong body of evidence showing that investment in high performance working practices, for example in leadership and management development, apprenticeships and other training programmes, smart job design and flexible working, can help boost workplace efficiency and outcomes.

The Resolution Foundation concludes that any benefits to be gained by UK-born low paid workers, (in terms of less competition for low paid jobs), from a fall in migration, will pale in comparison to the general wage slowdown predicted over coming years. The latter, will they say, be hardest borne by those with the lowest earnings.

The effect of EU migration on specific sectors in London

The following section considers the effect of EU migration on the hospitality sector and the NHS in London. It will identify some of the factors behind why the share of EU-born workers in both sectors has grown in recent years, and what restrictions on the free movement on EU labour could have for both sectors in the future.

Hospitality

The UK’s hospitality sector[27] has grown significantly in recent years. Between 2010 and 2014, the number of jobs has increased from 2.6 million to 2.9 million; only the business services sector has seen larger employment growth in the same period.[28] London has the highest share of UK hospitality employment, representing almost a fifth of total employment in the sector (520,000 jobs). London also represents almost a quarter of the total gross value added (GVA) of the industry.

The hospitality sector’s growth has seen an increase in the proportion of EU-born workers in the industry. Since 2004, the share of foreign-born workers in the sector has increased from 19 per cent to 28 per cent in 2014. While migrants from outside the EU make up the largest share of foreign workers, eastern European migrants have seen the largest recent increase, making up seven per cent of the total UK hospitality workforce in 2014. Almost three quarters of all foreign-born workers in hospitality are employed in London.[29]

Qualitative research suggests some EU workers in the hospitality sector are overqualified. Analysis by the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) on the impact of free movement on the labour market incorporated interviews with employers in a number of sectors, including hospitality. The research found examples of EU workers with skill levels above those required for the job they were doing.[30]

There are number of reasons why some EU workers take jobs below their qualification level. According to academic research, language difficulties, non-recognition of qualifications, recruitment discrimination, and ease of entry into certain industries are all possible causes behind why the skills of some EU workers are not always properly matched.

UK-born workers in the hospitality sector could be losing out because of competition from higher skilled foreign migrants. NIESR’s research found some evidence of faster rates of progression for migrants in the sector, compared to UK-born workers. According to one food and drink employer interviewed as part of NIESR’s research, higher rates of progression among migrant employees had caused some resentment from UK workers who felt they had been overlooked.[31]

Flexibility and availability was more likely to explain the hospitality sector’s reliance on EU workers than a skills deficit. According to NIESR’s research, employers in the hospitality sector did not recruit EU migrants because of specific skills shortages but because of a general shortage of UK-born applicants. Flexibility was also seen as an important factor. The needs of employers in low-skilled sectors have been well-matched by foreign workers. Academic research suggests EU workers are more likely to take temporary work with flexible or ‘zero hours’ contracts, which is less attractive to UK workers and problematic for those coming off benefits.[32]

Restrictions on the free movement of people from the EU could have a detrimental effect on the hospitality sector. If the government was to place similar restrictions on EU nationals as those currently imposed on non-EU workers, many of the jobs currently filled by EU workers in the hospitality sector would be excluded. According to research by the Social Market Foundation only a negligible number of jobs would meet the three requirements of the Tier 2 visa (see box 1 (p.12)).

The British Hospitality Association has said restrictions on free movement of people from the EU would be “catastrophic” for the hospitality sector. Ufi Ibrahim, chief executive of the British Hospitality Association, said any restrictions on migrant labour could force small businesses to close. She said the sector had told government it needed more than 100,000 visas a year once Britain exits the EU.[33]

NHS

Foreign-born workers make up a significant proportion of NHS staff in London. Around a quarter of London’s NHS workforce is non-UK born. EU nationals make up approximately ten per cent of London’s NHS workforce, compared to five per cent in the rest of England. The breakdown of EU-born doctors and nurses is broadly the same: 13 per cent in London compared to around 4 per cent in England.[34]

Numbers of EU-born nurses have risen at a time when the numbers of UK-trained nurses has fallen. According to NHS data, the number of EU nationals working as nurses and midwives has increased at a historically rapid rate, while the number of nurses trained in the UK has dropped. In July 2016, the government announced that it would be replacing nursing bursaries with student loans from August 2017.[35] The Mayor of London and the London Assembly wrote to the Department of Health to ask for the plans to be stopped because of the impact it would have on nursing students studying in London.[36] Without the increase in the number of nurses and midwives from the EU, overall nursing numbers would have fallen rather than remained relatively flat in recent years.

Restrictions on free movement of people from the EU could exacerbate staffing pressures in the NHS. In 2014, there was a six per cent shortfall (around 50,000 full-time equivalents) between the number of staff providers of health care services needed and the number in post, with large gaps in nursing, midwifery and health visitors. Similar problems exist in the social care sector, which has an estimated vacancy rate of five per cent. High turnover is also an issue, with an overall turnover rate of 25 per cent (which equates to around 300,000 workers leaving their role each year).[37]

The UK’s social care workforce is also likely to face significant shortfalls if there are restrictions on free movement of labour. Analysis by ILC-UK, a think-tank, found the social care sector could face a staff shortfall of more than a million by 2037, with London and the South-East the regions most likely to be affected.[38]

NHS leaders have sought to reassure EU staff working in the health service. Following the announcement of the referendum result, Sir Bruce Keogh, the NHS England Medical Director, said NHS leaders should “send out a message to European staff working in the health service that they are valued and welcome in the wake of the EU Referendum result.”[39] And Danny Mortimer, Chief Executive of NHS Employers, said “leaders across the NHS need to let the EU nationals in their teams know how valued this contribution will continue to be.”[40]

EU medical staff could be given automatic rights to UK citizenship. The Institute for Public Policy Research said EU nationals who work as doctors, nurses and physiotherapists should be given UK citizenship to prevent a post-EU exit “brain drain.” The IPPR said if EU nationals seeking citizenship face lengthy delays it could harm the UK economy and leave public services, such as the NHS, vulnerable.[41]

Options for future immigration policy

Currently, non-EU migration is managed by a visa system. There are two tiers for long-term work. Tier 1 visas are given to “high value migrants”: individuals must have either £200k to invest through the entrepreneur route, £1 million to invest, or meet “exceptional talent” rules. The more common route is Tier 2 (see box 1). Recently, the number of Tier 2 visas granted has risen slightly, while Tier 1 visas have fallen sharply. In the year to end June 2016, the majority of visas granted were Tier 2.[42]

The current Tier 2 (General) visa system for non-EU workers

For non-EU workers wishing to work in the UK, the main current visa route is known as Tier 2 (General). Under Tier 2 there are two principal ways in which employers can recruit non-EU workers:

Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT): Employers can bring a worker in from outside the EU if there is no suitably qualified worker within the UK or EU. Employers must advertise the vacancy in the UK for 28 days. This is the most common route, accounting for 92 per cent of Certificates of Sponsorship in 2015.

Shortage Occupation List: If the occupation is on the Shortage Occupation List, employers do not have to down the RLMT route. Occupations on the list must be skilled and experiencing a national shortage. Recent examples of such occupations include scientists, engineers and medical practitioners.

Under Tier 2 (General), migrants must earn at least £20,800 per annum and be in a graduate-level role, as defined in the Code of Practice for Skilled Workers. Tier 2 visas are usually valid for a maximum of six years. After this, to apply for permanent residency the worker must earn at least £35,000 per annum.

If Tier 2 conditions were imposed on future EU workers, a number of jobs currently filled by EU workers would not meet them. Research by the Social Market Foundation suggests three quarters of jobs carried out by EU workers in London (approximately 470,000) would not meet the Tier 2 visa conditions. Part-time workers would also lose out, as only 1per cent of part-time EU workers would meet the salary requirements compared to around 14 per cent of full-time EU workers.[43] Analysis by Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr) estimates that if London’s EU workforce had been subject to Tier 2 restrictions from 2010 to 2016, it would be 145,000 lower.[44]

A uniform immigration policy could have a negative effect on London’s GVA and tax receipts. According to analysis by Cebr, if immigration policy followed current Tier 2 visa targets, the GVA loss to London of restricted access to foreign labour would be an estimated £6.9 billion per year. And the loss of taxation receipts to the UK exchequer could be over £2 billion by 2020.

There are many possible ways immigration policy could be reconfigured. The occupational or earnings criteria used for migrants could be revised to at least partly compensate for losing EU migrants, or an overall quota for EU nationals could be set, with no restrictions on occupations or earnings. Alternatively, sector-specific quotas could be developed, which would only be open to EU migrants. Or, the government could relax controls on skilled non-EU migration, while reducing EU migration.

Government has so far sent mixed messages as to how EU migration will be managed in the future. The Home Secretary has suggested skilled EU migrants may have to apply for visas with conditions similar to those placed on migrants from outside the EU.[45] But the Chancellor has also said high-skilled migrants could be exempt from controls. He said the government would use control over free movement “in a sensible way that will facilitate the movement of highly-skilled people between financial institutions and businesses to support investment in the UK economy.”[46]

The government could impose a tax on UK businesses for every skilled EU worker they hire. Robert Goodwill MP, Minister of State for Immigration, said, in evidence to the House of Lords EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee, that a £1,000-a-year levy, which is being imposed on non-EU workers from April, could be extended to EU workers. He said this would “be helpful to British workers who feel they are overlooked.”[47] The move would be significant as it would mean EU workers would not be treated differently to non-EU workers after EU exit. However, a government spokesperson has since said the policy was “not on the agenda.”

A number of studies have looked in detail at immigration policy post-EU exit. The rest of this section looks at two: David Goodhart’s paper for Policy Exchange, Immigration and integration after Brexit, and British Future’s report, Britain’s immigration offer to Europe. David Goodhart and Sunder Katwala, Director of British Future are both guests at this meeting.

Immigration and integration after Brexit

David Goodhart’s paper for Policy Exchange considers how the EU exit vote is an opportunity to “reboot” policy thinking around immigration and integration. ( see App 1) The report’s main arguments are:

Freedom of movement should be replaced with a work-permit controlled movement of labour similar to the one used for non-EU workers but with more favourable terms for EU workers.

The UK government should create a new department of state for immigration and integration.

A commission should be setup to review how employers can be incentivised to hire and train UK citizens.

Automation could compensate for the potential loss of EU workers in low-skilled employment.

A population register and two-tier citizenship should be introduced to enable benefits to be directed to permanent residents.

Britain’s immigration offer to Europe

British Future’s report ( see App2) argues single market access and immigration reform is not a zero-sum game. The report states that while keeping free movement might be politically impossible, a constructive new partnership with the EU can be formed. The report presents a policy framework to achieve this. The report also puts forward six “tests” which should be met in the government’s EU exit negotiations.

The report proposes a preferential migration system for EU nationals. The system would comprise of three tiers. The first tier would be a “global talent route” for the “brightest and best” from any country to move to the UK. The second tier would consist of a reciprocal free movement route with an income or skills threshold, which would enable EU nationals to move to the UK without a visa providing the jobs they took met certain criteria. The third tier would comprise sector-based quotas to fill low-skilled and semi-skilled jobs. The three-tier system would operate alongside a reciprocal visa-free travel across the UK and EU and a deal to secure the rights and status of EU nationals already living in the UK.

The report also considers other policy options for future migration policy, including a regional immigration system, but argues these would fail its tests. The GLA Oversight Committee’s EU exit working group recently held a meeting to discuss the potential for a London visa. The proposal had support from the London Chamber of Commerce and City of London, who have both published reports on how devolved immigration policy. However, British Future argues a regional immigration system would be difficult to enforce and could lead to a rise in illegal working. The report also argues that geographic demarcation would risk distorting fair competition. For example, employers in Dartford would face recruitment restrictions that did not apply to employers in Bexley.

Appendix 1

A summary of Britain’s immigration offer to Europe by David Goodhart (Policy Exchange)

David Goodhart’s paper for Policy Exchange considers how the EU exit vote is an opportunity to “reboot” policy thinking around immigration and integration. The paper is divided into five sections: freedom of movement; bureaucracy; employability of UK citizens; social infrastructure; and long-term planning.

Freedom of movement

Goodhart states the principle of free movement has changed radically since the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. Before the Treaty, it was labour that moved and not citizens, and workers had to have job offers. But since 1992, European citizens have been able to move and carry with them almost all the rights and privileges national citizens have. He advocates a work permit system similar to the one used for non-EU workers but with more favourable terms for EU workers. However, he argues for a sector-by-sector approach to reduce overall numbers of EU workers.

Bureaucracy

Goodhart states the UK government should create a new department of state for immigration and integration. He argues there is a “powerful national mandate” to reduce immigration and this mandate “needs to be heard louder throughout government.” He states the current work permit system could be improved by allowing more self-administration (within a cap) for large organisations such as universities, which would enable more resources to be directed to small firms which only use the system occasionally and can find the process expensive and onerous.

Employability of UK citizens

Goodhart suggests a commission should be setup to review how employers can be incentivised to hire and train UK citizens. Goodhart believes the UK’s flexible labour market has many advantages but has left many British employees without the necessary technical skills (he cites the decline in HNDs and HNCs) allowing employers to “cherry pick from the European labour market.” He believes the private sector has failed to invest in Stem (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and IT skills because it is too easy to bring in trained people from outside the EU.

Goodhart also argues that automation could compensate for the potential loss of EU workers in low-skilled employment. He recognises that while British workers are prepared to do “tough and anti-social work”, the “insecure and episodic” nature of many jobs in construction, food processing and agriculture are unattractive to British workers even if the jobs are better paid. Goodhart refers to Japan’s highly automated agricultural sector and the potential for greater automation in factories. He also refers to Singapore which offered grants and loans to labour intensive business to smooth the process of reducing its dependence on foreign labour.

Social infrastructure

Goodhart states that public spending cuts should be subject to an immigration audit. He argues constraints on public spending have resulted in higher immigration. He refers to cuts in nurse training which has seen more nurses coming from Portugal or Poland. He states the same impact has happened for care workers and teaching staff in shortage subjects.

Goodhart suggests a revised version of the Migration Impacts Fund (MIF) should be introduced as part of a boost to public spending. The original MIF was introduced by Labour in 2008 to provide financial support to local authorities in areas of high immigration. The scheme was ended in 2010 before being reinstated by the Conservative government in 2015. Goodhart argues the system has flaws but if properly managed could be a “useful innovation in local demographic management.” He believes more funding is needed (the MIF budget was £35 million a year in 2008) but local authorities should have to bid for top-up money to expand the provision of GP surgeries, A&E departments and public housing.

Long-term planning

Goodhart argues that a population register and two-tier citizenship should be introduced to enable benefits to be directed to permanent residents. He believes an overhaul of migration statistics and oversight of movement across borders is required. He argues for the introduction of a “Scandinavia style population register for all citizens (and non-citizens) incorporating a unique person number.” He states the system could be based on NHS registration, and biometric residence permits used for some non-EU temporary migrants could be extended into “some kind of ID card for all those without permanent residence.” Goodhart also argues for a more formal distinction between full and temporary citizenship. He states the lack of a clear distinction has led to unnecessary resentment in communities. He believes a temporary citizen should not have full access to social and political rights and should leave after a few years. He argues this would enable rights, benefits and integration efforts to be concentrated on those making a full commitment to the country.

Appendix 2

The six “tests” set out in British Future report, Britain’s immigration offer to Europe

Fair to migrants and receiving communities

Migrants should be offered routes to settlement and citizenship, while the impacts on public services, housing, and employment opportunities in communities should be mitigated and managed.

Work for the economy

The system should work for both employers, the economy, all sectors and in all parts of the UK with an administrative system that is as simple as possible.

Deliverable as policy

The reforms should void imposing unnecessary burdens on employers, the Home Office and other parts of the government or migrants themselves. The reforms should be enforceable so as not to lead to an increase in informal economy or damage public trust in the immigration system.

Able to secure public confidence and consent

The Leave vote was “not a vote for indiscriminate immigration crackdown”. The majority of the British public want to keep highly skilled migration. There is a stronger desire to reduce low skilled and semi-skilled migration, with an instinct towards moderation for some specified types of work, i.e. not reducing care workers for the elderly. A key test for future immigration policy is the extent to which it is capable of securing public confidence and consent.

Political viability in the UK

The reforms should aim to secure broad support in Parliament, across the mainstream party political spectrum, and across the different regions and nations of the UK. It should seek to command the support of voters from both sides of the referendum.

A positive offer that can win support in the EU too

Whatever system is chosen, it should be able to benefit both the UK and the 27 remaining EU member states.

[1] ONS data uses the United Nations definition of an international long-term migrant, where a long-term international migrant is a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for a period of at least 12 months.

[2] Migration Statistics Quarterly Report ONS (December 2016)

[3] Migration Statistics Quarterly Report ONS (December 2016)

[4] Migration Statistics Quarterly Report ONS (December 2016)

[5] The ONS publishes short-term migration figures for England and Wales, using three definitions of a short-term migrant: those staying for a minimum of one month, three months, and the narrower UN definition of those that migrate for 3 to 12 months for work and study

[6] 45 per cent (516,000) were visits by non-EU citizens, 41 per cent (475,000) by EU citizens and 14 per cent (167,000) by British citizens

[7] Short-term international migration annual report: mid-2014 estimates ONS (May 2016)

[8] Short-term international migration annual report: mid-2014 estimates ONS (May 2016)

[9] Short-term international migration annual report: mid-2014 estimates ONS (May 2016)

[10] NIESR Review No. 236 May 2016

[11] Note on the difference between National Insurance number registrations and the estimate of long-term international migration: 2016 ONS (2016)

[12] Keep foreign students out of net migration, PM urged The Times (19 December 2016)

[13] London Assembly Plenary 2 November 2016

[14] Nationality has been used as a measure rather than country of birth to identify those potentially vulnerable to changes to immigration laws

[15] Population in the UK by nationality, Annual Population Survey 2015, ONS

[16] EU citizens in UK fear for jobs ahead of Brexit talks The Financial Times (28 October 2016)

[17] Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee – Uncorrected oral evidence: Brexit: UK-EU Movement of People

[18] This data uses country of birth rather than nationality as a measure and so also includes foreign-born individuals who have become UK citizens

[19] Number of jobs by country of birth of job holder, Annual Population Survey 2015, ONS

[20] Annual Population Survey 2015, ONS

[21] Annual Population Survey 2015, ONS

[22] English Health Service’s Electronic Staff Record

[23] London tech heavyweights call for European talent to remain in the capital following Brexit vote, City AM (1 July 2016)

[24] Economy Committee 13 December 2016

[25] Annual Population Survey 2015, ONS

[26] Immigration and the UK Labour Market CEP (2015)

[27] The hospitality industry includes enterprises that provide accommodation, meals and drinks in venues outside of the home

[28] The economic contribution of the hospitality industry Oxford Economics (2015)

[29] The economic contribution of the hospitality industry Oxford Economics (2015)

[30] The impact of free movement on the labour market: case studies of hospitality, food processing and construction NIESR (2016)

[31] The impact of free movement on the labour market: case studies of hospitality, food processing and construction NIESR (2016)

[32] Migrants in low-skilled work, Migrant Advisory Committee, 2014

[33] Hospitality industry demands 100,000 Brexit work permits a year Sky News (23 December 2016)

[34] English Health Service’s Electronic Staff Record

[35] https://www.rcn.org.uk/nursingcounts/student-bursaries

[36] https://www.rcn.org.uk/news-and-events/news/mayor-of-london-backs-bursary-campaign

[37] Five big issues for health and social care after the Brexit vote The Kings Fund (30 June 2016)

[38]Brexit and the future of the migrant social care workforce ICL-UK (2016)

[39] NHS must make EU staff feel ‘valued’, says Keogh Nursing Times (24 June 2016)

[40] NHS must make EU staff feel ‘valued’, says Keogh Nursing Times (24 June 2016)

[41] Becoming one of us: Reforming the UK’s citizenship system for a competitive, post-Brexit world IPPR (2016)

[42] Immigration statistics quarterly release

[43] Working Together? The impact of the EU referendum on UK employers Social Market Foundation (2016)

[44] Working Capital Cebr (2016)

[45] Amber Rudd vows to stop migrants ‘taking jobs British people could do’ and force companies to reveal number of foreigners they employ The Daily Telegraph (4 October 2016)

[46] European bankers will be exempt from migration curbs after Brexit, The Daily Telegraph (8 September 2016)

[47] House of Lords EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee 11 January 2017